As a global seismic velocity discontinuity, the Moho is recognized as the boundary between the Earth's crust and the upper mantle. The oceanic crust-mantle boundary is expected to produce impulsive reflection in seismic reflection profiles, because of the contrasting seismic velocity and density between gabbros in the lower crust and peridotites in the upper mantle. However, at fast- and intermediate-spreading ridges with full spreading rates larger than 55 mm/yr, the Moho reflections are highly variable and can be categorized as impulsive, shingled, diffusive, and weak or invisible (Carton et al., 2020). The mechanisms of complex Moho reflections at fast- and intermediate-spreading ridgesremain debated.

Petrological studies have identified two types of the oceanic crust-mantle boundary: a sharp boundary characterized by gabbros directly overlying peridotites, and a layered boundary consisting of gabbro sills interlayered with dunites and harzburgites. At fast- and intermediate-spreading ridges, seawater-derived fluids can penetrate down to the crust‐mantle boundary through fractures and faults, resulting in hydrothermal alteration of the lower oceanic crust and uppermost mantle. The near‐axis hydrothermal circulation leads to rapid cooling of the oceanic crust, thus affecting the lower crustal accretion process (Faak et al., 2015; Maclennan et al., 2005). However, the extent and distribution of the hydrothermal circulation at fast- and intermediate-spreading ridges remain poorly constrained, which hampersour understanding of the formation and evolution of the oceanic lithosphere.

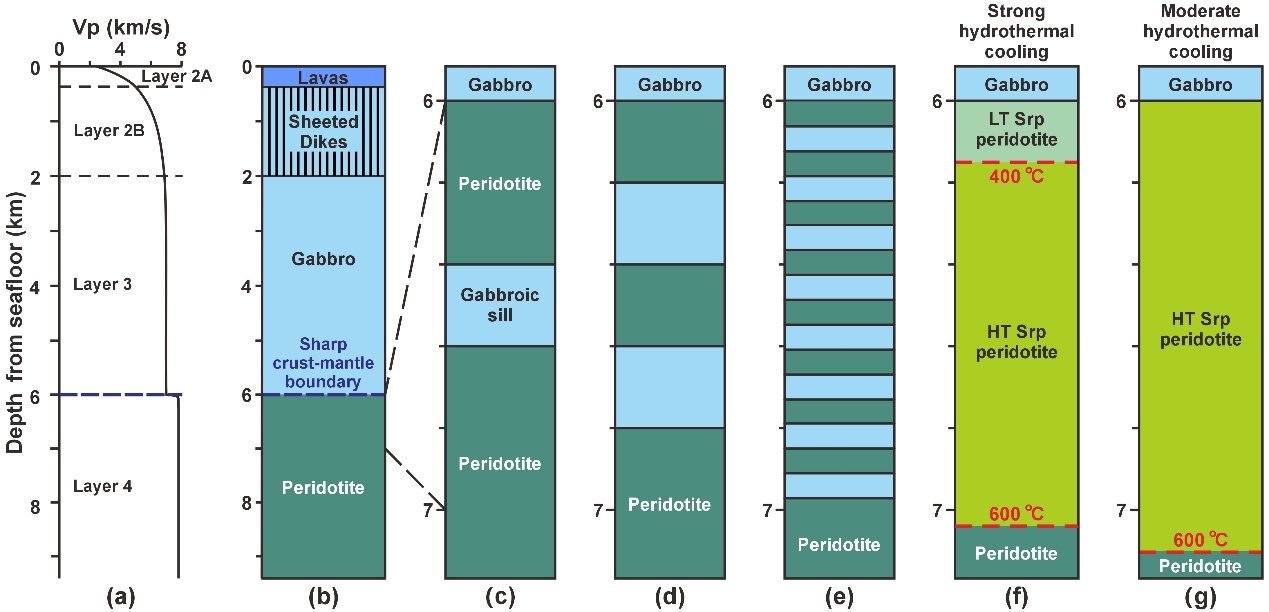

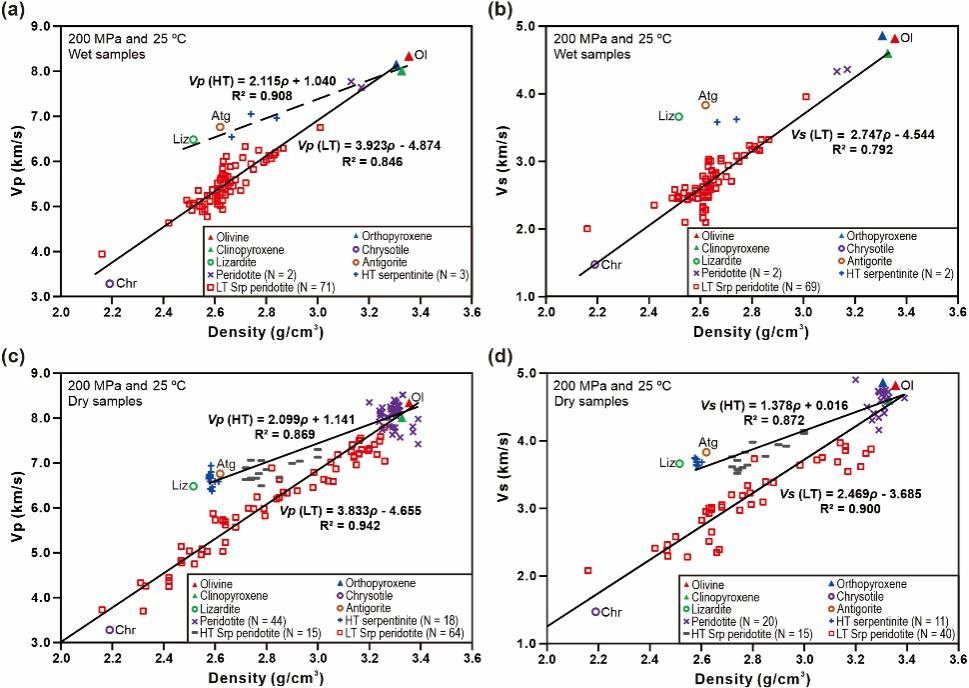

Here we constructed petrological models of the oceanic crust-mantle boundary with different structures and different types of serpentinization, according to the thermal structure of the East Pacific Rise calculated by Maclennan et al. (2005) (Figure 1). Based on laboratory velocity measurements, we obtained the pressure and temperature dependence of seismic velocities for major oceanic rocks (i.e., basalts, diabases, gabbros and peridotites). In particular, we calibrated the relationship between serpentinization degree, density, and seismic velocities of peridotites at 200 MPa (Figure 2). These results enabled us to construct seismic velocity and density models for fast- and intermediate-spreading mid-ocean ridges.

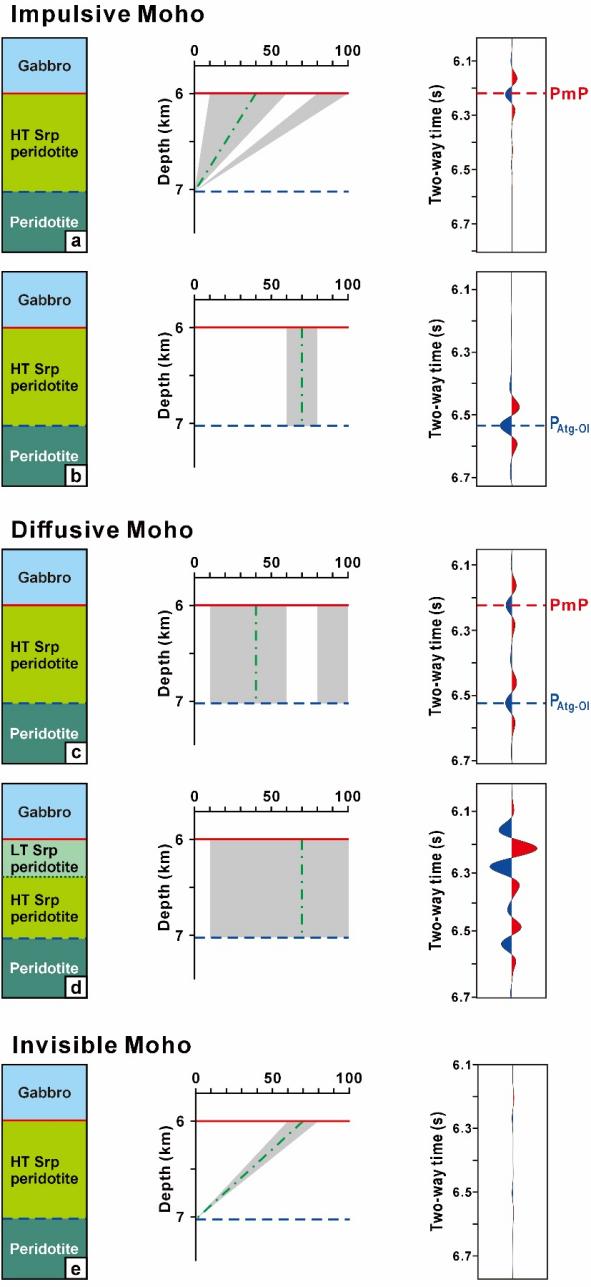

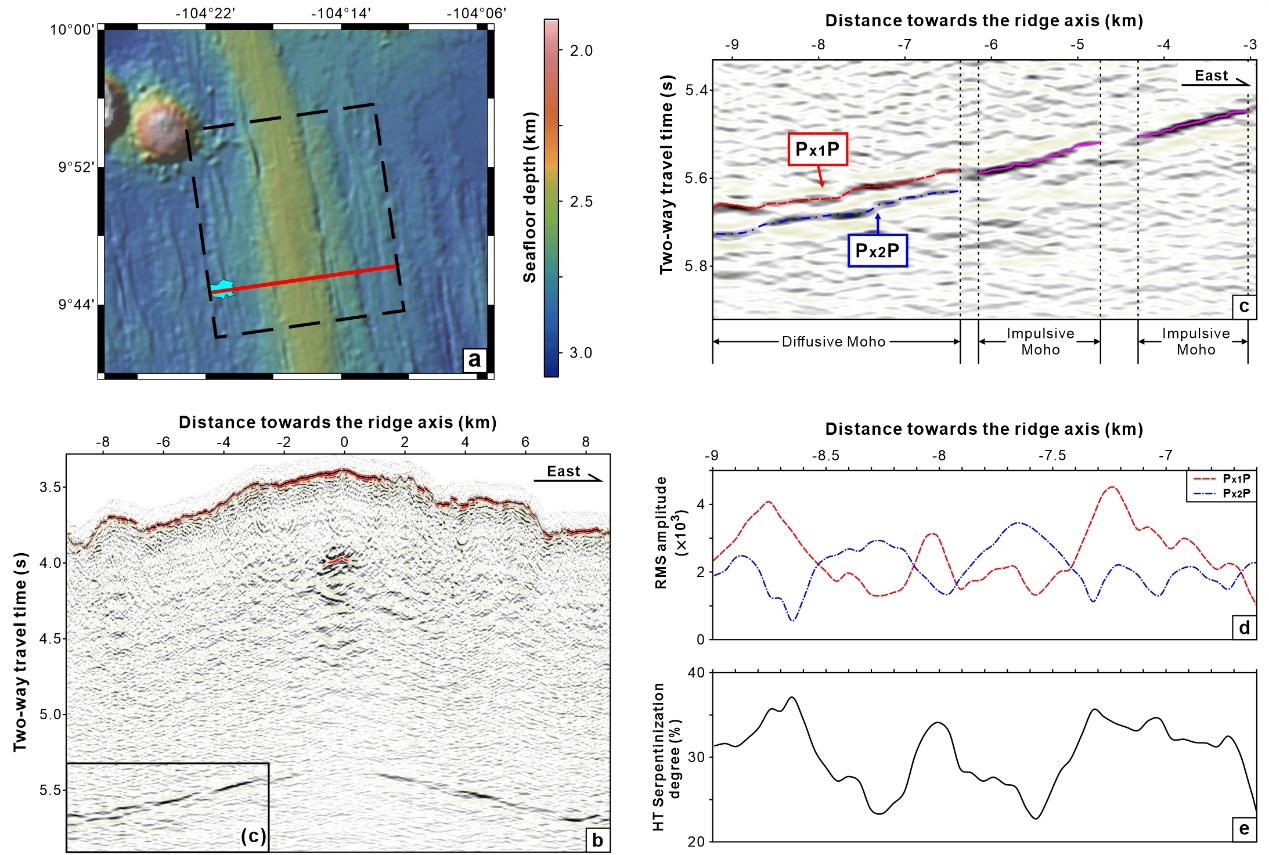

Synthetic seismograms demonstrate that the oceanic Moho reflections at fast- and intermediate-spreading ridges are controlled by both structure and serpentinization of the crust-mantle boundary (Figure 3). Our results suggest that the diffusive Moho at 6–9 km west of the East Pacific Rise 9°44′N can be interpreted by averaging 30% HT serpentinization in the uppermost mantle, indicating deep and localized off‐axis hydrothermal circulation (Figure 4). The Moho reflection characteristics provide valuable insights into crust-mantle interactions, thereby shedding light on the interplay between magmatic, tectonic, and hydrothermal processes in the oceanic lithosphere.

This studyentitled "Structure, serpentinization and seismic reflectivity of the crust‐mantle boundary at fast‐ and intermediate‐spreading ridges " was published in Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth.PhD student Jiabin Zhao is the first author, with Prof. Qin Wang as the corresponding author. Nanjing University is listed as the first affiliation. Co-authors include Prof. Youyi Ruan (Nanjing University), Dr. Wenbin Jiang (Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey), and Prof. A. Alexander G. Webb (Freie Universität Berlin, Germany).

The study was jointly supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFF0803304), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 41825006) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42506067).

Citation: Zhao, J., Wang, Q., Ruan, Y., Jiang, W., & Webb, A. A. G. (2025). Structure, serpentinization and seismic reflectivity of the crust-mantle boundary at fast- and intermediate-spreading ridges. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 130, e2025JB032120. https://doi.org/10.1029/2025JB032120

Figure 1. Seismic profile and petrological models of the oceanic lithosphere at a fast-spreading ridge. (a) Seismic layers of the oceanic lithosphere (after Vithana et al., 2019), (b) petrological model of the Penrose-type oceanic lithosphere with a sharp crust-mantle boundary (after Dilek & Furnes, 2014), (c) a layered crust‐mantle boundary with one 200‐m‐thick gabbroic sill, (d) two layers of 200‐m‐thick gabbroic sills, and (e) eight 60‐m‐thick gabbroic sills, (f, g) serpentinization for a sharp crust‐mantle boundary with strong and moderate hydrothermal cooling, respectively. The predicted depths for the 400°C and 600°C isotherms by Maclennan et al. (2005) correspond to the boundaries for low‐temperature serpentinization (LT Srp) and high‐temperature serpentinization (HT Srp), respectively. Note that strong hydrothermal cooling results in a downward transition from low- to high-temperature serpentinization, whereas moderate hydrothermal cooling produces solely high-temperature serpentinization.

Figure 2. Correlation between seismic velocities and density of serpentinites and serpentinized peridotites at 200 MPa and room temperature.

Figure 3. Serpentinization effects on the sharp crust‐mantle boundary and the Moho reflection from this study. Left panels show serpentinization types in the upper mantle; middle panels show degree of serpentinization (gray shading); right panels show zero‐offset synthetic seismograms. Green dashed lines in middle panels mark serpentinization degrees corresponding to the synthetic seismograms. Depth from the seafloor is assumed as 6 km for the bottom of the lower crust.

Figure 4. Moho reflections at the East Pacific Rise. (a) Bathymetry map of the East Pacific Rise between 9°40′N and 10°N latitude (Ryan et al., 2009). (b) The multichannel seismic profile across the East Pacific Rise. (c) Expanded view of the Moho at the west flank of the East Pacific Rise. (d) The root‐mean‐square (RMS) amplitude computed along the reflected phases Px1P and Px2P using a 20‐ms window. (e) HT serpentinization degree inferred from RMS amplitude ratio between the Px1P and Px2P.

Reference:

Carton, H., Carbotte, S., Mutter, J., Canales, J., & Nedimovic, M. (2020). Processed 3‐D multi‐channel seismic data volume for the East Pacific Rise 9°42’–9°57’N from the MGL0812 survey (classical time processing by H. Carton) [Dataset]. Marine Geoscience Data System. https://doi. org/10.1594/IEDA/326492

Dilek, Y., & Furnes, H. (2014). Ophiolites and their origins. Elements, 10(2), 93–100. https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.10.2.93

Faak, K., Coogan, L. A., & Chakraborty, S. (2015). Near conductive cooling rates in the upper‐plutonic section of crust formed at the East Pacific Rise. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 423, 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.04.025

Maclennan, J., Hulme, T., & Singh, S. C. (2004). Thermal models of oceanic crustal accretion: Linking geophysical, geological and petrological observations. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 5(2), Q02F25. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003GC000605

Ryan, W. B. F., Carbotte, S. M., Coplan, J. O., O’Hara, S., Melkonian, A., Arko, R., et al. (2009). Global Multi‐Resolution Topography synthesis. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 10(3), Q03014. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GC002332

Vithana, M. V. P., Xu, M., Zhao, X., Zhang, M., & Luo, Y. (2019). Geological and geophysical signatures of the East Pacific Rise 8°–10°N. Solid Earth Sciences, 4(2), 66–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sesci.2019.04.001